How do you get a realistic image of the person in front of you? How can you avoid making assumptions and learn to listen to what they need?

It’s the antenatal booking appointment. The woman in front of you is within the first 10 weeks of her pregnancy. You discuss her health, her marital status, whether this is her first child and, if not, whether the previous one was a vaginal or caesarean birth. You take her age and weight, discuss blood tests and urine samples, take her blood pressure and ask if she has any questions. You make notes in her orange folder. You try to put her at ease by being friendly and kind. The appointment is over and she leaves the room. What do you really know about her?

This question has been a constant in midwifery – in a role that literally means being ‘with woman’, it’s an inherent position of trust and intimacy.

“You don’t know what they’ve been through just to get there,” says Kaat De Backer, midwife and NIHR doctoral research fellow in maternal and perinatal mental health at King’s College London. Kaat has authored an NIHR-funded MUMS@RISC study of the maternity experiences and perinatal outcomes of mothers facing removal of their infant due to social care proceedings.

“The main takeaway from all of my research is that kindness is crucial, but there are system challenges that need to be addressed, and they take resources. You need to provide holistic trauma-informed care for these women and make services join up.

“Is it fair to expect a woman to attend appointments while she doesn’t have the money to pay for the bus fare to come to the hospital and to go to all these different services? I did a confidential enquiry with the MBRRACE-UK team, and when we did a deep dive into these women’s medical notes, we could see that professionals quickly jump to conclusions of poor attendance and poor engagement. They lose that kindness and the trauma-informed approach about what’s actually going on in these women’s lives.”

Be the change

But where the system fails, midwives can help. “One woman asked for help on the maternity ward as she was about to be discharged home without her baby,” says Kaat. “She asked for some support for her mental health and was given the number of a crisis team on a scrap of paper and told, ‘Oh, just call this number.’

“In contrast, the midwife who was there went above and beyond. She asked, ‘Can I do anything in terms of taking pictures?’ She organised the baptism for the baby, because that was really important for that woman. Those are those acts of kindness that will stay with her forever, and they don’t necessarily cost any money.”

It’s important to note too that women may be hesitant to engage with the service because of previous trauma or life experiences. Kaat says: “Women who have contact with social care for their children often come from a background of childhood adversity and abuse themselves, and that has a huge impact on how you view what a healthy relationship is, and who you can trust. Somebody from a life of adversity might be finding ways to cope with pain and trauma and, having no other means to do that, may turn to substances.

“Once you start to think in that way, it becomes easier to be kind and compassionate; if you take away the blame, the guilt and the punitive approach, I think it becomes a lot easier to be kind. You don’t have to sit in judgement; we can just provide good, compassionate care, void of judgements and stigma. It’s important to get it right for these women because of compounded trauma they’ve had throughout their lives, then the removal [of their baby] on top of that.”

A friend in need

What is clear is that having someone to listen and care can make a huge difference, even in the most upsetting circumstances. Naomi Delap is the director of Birth Companions, a charity set up to support disadvantaged women during pregnancy, birth and early motherhood. It recognises that women with past trauma can respond to health services, and any institution or authority, with mistrust and fear.

One really good example of its work is the Izzy Project in Hackney – a pilot service that supports pregnant women who have children’s social services involvement and who are at risk of separation from their baby. It was developed with 40 stakeholders including local midwives, social workers and those working in perinatal mental health. It also included women with lived experience – those who didn’t need direct support anymore but still wanted to be involved.

Naomi says: “When women are in the process of engaging with children’s social care – and a decision [about whether a baby stays with the mother] is never made until after the baby is born – it’s a period of great stress and uncertainty. How a woman has been engaging with services during her pregnancy can sometimes make a real difference.”

Women in these situations can be reluctant to interact even with Birth Companions. Naomi notes they may feel they have too many professionals, services and appointments already and may not feel able to cope with another. “It’s done on the basis of being woman-centred, so women can engage when they want and how they want,” she says. “It’s about offering emotional and practical, but also advocacy, support. Very often, coordinators are going with women into meetings with children’s social care or to appointments. They’re attending court hearings to ensure that women understand what’s going on. They have someone by their side.”

They help bridge the gap between the women’s hopes and needs, and what the system is able to offer in terms of the best outcome for all.

“Every midwife will, at some point in their career, know a woman who they have to refer to children’s social care,” says Naomi. “And I think, unfortunately, there’s probably quite a lot of misunderstanding and stigma around people being in that situation. If midwives can view that woman with a trauma-informed approach, asking ‘What’s happened to that person?’ rather than ‘What’s wrong with that person? Why are they so difficult?’, that would be good. They need to be understanding and compassionate.”

Kaat: “You don’t have to sit in judgement; we can just provide good, compassionate care, void of judgements and stigma”

Just ask

Being able to support someone through a significant point of crisis may not be the day-to-day experience of many midwives, but everyone will understand the importance of communication.

Teri Gavin-Jones is a midwife, midwife educator and senior clinical lead for Suffolk and North East Essex Local Maternity and Neonatal System. In 2021, she asked 40 midwives: ‘Are you comfortable having conversations around ethnicity?’ “52% were comfortable, but that left 48% who told me they were uncomfortable discussing it,” she says. “I also asked: ‘Do you discuss the risks associated with ethnicity or skin colour with women?’ Only 30% of midwives said they did.”

Midwives and maternity support workers told her: ‘We don’t know how to start the conversation. We don’t want to offend people, or we feel that we do not have enough cultural understanding of this community.’

It set in motion something great. “The community, who are experts by experience, offered to inform and educate the staff; that’s when the idea of films called It’s OK to Ask was conceived,” Teri says. “What I’ve learned is that they have stories that they want to share about their experiences of using maternity services.”

The films don’t just cover feeling confident to discuss ethnicity. Teri says: “One of the organisations we work with is called Survivors in Transition, and it supports adults who have suffered sexual violence as children. We know that pregnancy and childbirth can be a trigger for those survivors. The films offer an insight into this cohort, who can feel unheard.”

There is also a ‘grandmas’ group’ (see below).

Grandmothers’ wisdom

There’s a theory that menopause is an evolutionary trait to keep grandmothers alive as long as possible for the benefit to society of their lifetime’s worth of knowledge (and there’s a funny TikTok video of Professor Roy Casagrande noting that men’s wisdom isn’t considered to be nearly as useful). While this is a much-debunked theory, it does highlight the power grandmothers have to educate.

PHOEBE is an Ipswich-based charity promoting health and equal opportunities for Black, Brown and mixed heritage women. Many of their community are survivors of domestic violence. Teri Gavin-Jones says: “What PHOEBE told us is when somebody flees and resettles, they leave behind all of their social network and their social support. As grandmothers are revered for their wisdom and status, they decided to create a grandmothers’ group.”

Fifteen grandmothers aged between 60 and 80 – mostly from the African continent, with some retired midwives – support young pregnant women and women with new babies and new families postnatally. Teri says: “They are this amazing group of strong women who are passing on their wisdom to the next generation without actually being related.”

The group is also able to disseminate important health information and dispel misinformation that can prevent women accessing the maternity care they need.

Being seen and heard

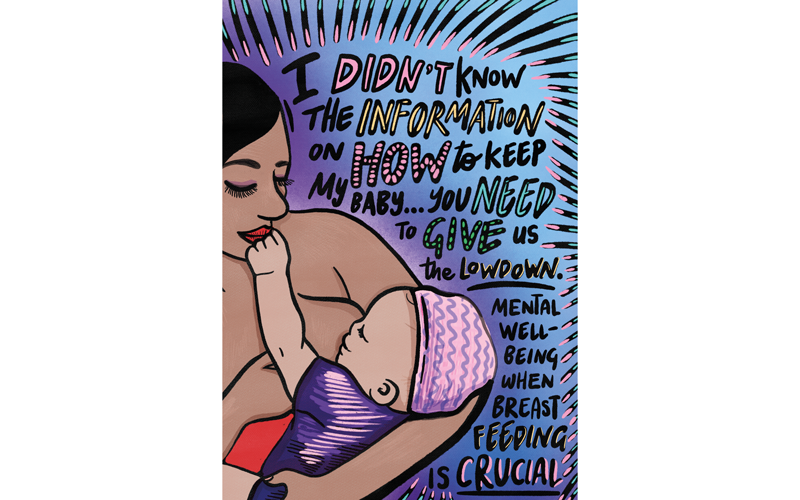

According to the Lost mothers report, imprisoned mothers who are separated from their babies at or around birth experience an overwhelming physical and emotional craving to care for their children, compounded by trauma, grief and the invisibility of their mental health needs.

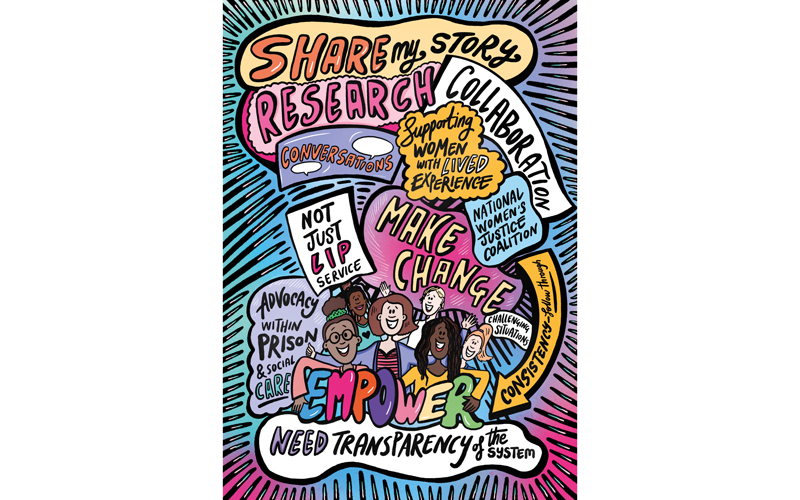

Led by the University of Hertfordshire and Birth Companions, 29 women who had experienced or were facing separation from their babies were interviewed – alongside 45 professionals including midwives – across five women’s prisons in the UK.

RCM fellow Laura Abbott, associate professor in research at the University of Hertfordshire and project lead, says: “Midwives can offer unconditional, respectful support that recognises the trauma and grief mothers experience during separation. By listening without judgement and validating a mother’s emotions, midwives help women feel seen and heard when their needs are often invisible within the system.

“Supporting mothers to create birth plans, discussing their wishes and explaining what will happen during and after birth can restore a sense of agency and dignity,” she explains. “Knowing what to expect and having their preferences respected, even in small ways, can help mothers feel less powerless.”

Facilitating meaningful goodbyes and memories is equally important. Laura says: “Midwives can support mothers to create keepsakes or rituals, such as writing a letter or poem to their baby, making a small item for the child to take, or keeping a blanket or first outfit as a memory. These acts can provide comfort and a tangible connection.

“Midwives can offer a safe space for mothers to express grief, anger or hope, and encourage participation in peer support groups or one-to-one conversations, reducing isolation and helping them process their emotions. They are well-placed to advocate for appropriate mental health support. By working closely with prison staff, social care and voluntary organisations, they can also help build a more compassionate, coordinated response to maternal separation, ensuring support is tailored.”

This heartbreaking set of circumstances also takes an emotional toll on the midwives supporting the mothers. The Prison Midwives Action Group was set up by Laura to connect prison midwives across the country, share best practice and discuss challenges. “This kind of professional community helps midwives process their own experiences, access advice and maintain the resilience needed to provide compassionate, informed care and advocacy for mothers in the prison system,” she says.

Ultimately, Laura says, midwives can provide the best care for new mothers in prison by consciously setting aside assumptions, listening deeply and without judgement, reflecting on their own biases and approaching every mother with empathy, respect and a commitment to trauma-informed, individualised support.

Midwives could be helping new mothers in prison facing compulsory separation from their babies; women facing possible separation from their babies in social care proceedings; women who are reluctant to engage with maternity services without it being clear why; or women with specific social and cultural needs. Whatever the case, it’s clear that building a picture of the person in front of you isn’t always straightforward, but is always necessary.

As RCM CEO Gill Walton told the conference in May: “Every single member of the midwifery community wants to see positive change in maternity services. We want to be able to spend time with women and to support them to make informed choices about their care. We want to have the time to address the real issues around perinatal mental health. We want to see every family leave our care whole and happy.”

How midwives can support

- provide trauma-informed, non-judgemental care

- empower women through choice and information

- facilitate meaningful goodbyes and memories (in cases of separation)

- support emotional expression and connection

- advocate for women’s needs

- promote collaboration and compassion.

FIND OUT MORE

The MUMS@RISC study concludes in August

Birth Companions’ Izzy Project

For the Birth Companions case study and more from Teri on the It’s OK to Ask project, visit here

Download the Lost mothers report or watch the plays at lostmothers.org